HOLLYWOOD RUSSIA

HOLLYWOOD RUSSIA

The White Emigration

Goes Hollywood

OLGA MATICH

The stereotype of the

Russian aristocrat in Paris turned cab driver is rivaled in Hollywood by the

figure of the aristocrat or tsarist general as movie extra reliving his past on

the silver screen. Joseph von Sternberg's silent film Last Command (1928),

in which the former commander-in-chief of the Russian armies becomes a lowly

extra in Hollywood, is exemplary of this émigré narrative. Emil Jannings played the general, for which he won the first

Academy Award for best actor. Real Russian generals appeared in the film in

anonymous bit parts, commodifying their personal historical experience. Stories

about Russian aristocrats and military men who had fought in the White Army and

lost power, prestige, and property as a result of Bolshevik victory were staple

currencies in Hollywood of the 1920s and 1930s.'

The American

fascination with Russian aristocracy led to the hyperinflation of its numbers.

An article in the New York Times about Russians in Hollywood in the

early 1930s claimed that "more than 2,500,000

aristocrats were exiled from Russia after the revolution. Fifteen hundred found

their way to Hollywood. Some of them are doing extra work in George Bancroft's The

World and the Flesh," a film set during the Civil War in General Wrangel's Crimea.2 The

author of the article apparently used the figure of all refugees after the

revolution, estimated between one and two million, as if to suggest that all

Russians who left after the revolution were aristocrats or at least members of

high society. Such was the popular view of the so-called White emigration, a

view reinforced by many of the Hollywood Russians themselves. White Army

officer turned bit player cum cab driver Alexander Woloschin

satirized the proliferation of aristocratic titles and illustrious identities

among them:

|

KOHeYHO, eCTb H CaM0313aHLIbI,

HM nepnT AHIIIb amepicatigm, H Haum "XAecTaxonm"

TyT — flpH pyCCKI4X — OT-leHb pe4Ko BpyT.

· • •

|

Of course, there are

also imposters, But only Americans believe them, Our "Khlestakovs" here —

Rarely lie in the

presence of Russians.

· • •

|

'For a discussion of the Russian

vogue in Hollywood during the 1920s and 1930s see Olga Matich, "Russkie

v Gollivude/Gollivud o Rossii," Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 54:2

(2002): 403-48. I would like to thank my

informants William Anoukichine, Marina A. Dakserhof-Golitsyn

(d. 2001), Margarita R. Gisetti, Vasilii

I. Koulaeff (d. 2003), Mike Protzenko,

and Luddie Waters (Liudmila

T. Ignatiev) for sharing with me their knowledge

about

the Russian community in Hollywood,

their memories of the past, and their archives.

2"Among

the Extras: War Veterans, Russian Expatriates, Authors Furnish

Atmosphere," New York Times, 20 March 1932, quoted in Gene Brown,

ed., Encyclopedia of Film 1926-1936, vol. 2 (New York, 1984).

The Russian Review 64 (April 2005): 187-210 Copyright 2005 The

Russian Review

188 Olga Matich

3,ziech BOIK —

"CAyAIHA B KoHBoe liapcitom','

Everyone "served in the Tsar's Convoy here,"

"Aio6umuem" CABIA B IIOAKy

I'ycapcxoM; Was known as "favorite" of the Hussar regiment;

Mx scex — "6cm.Acii

futtzietthype: All

"were feared by Hindenburg."

FIX

"3HaA CaHOBHIA3I

FleTep6ype:

All

"were renowned in high-ranking Petersburg,"

Bce "Bo /tucpitax KaK Roma 6bi.m47 Everyone

"felt at home in Palaces,"

Bce — Nati c Mapem

gacTeubico [MAW' Everyone "often drank tea with the

Tsar."

KpecTop. H 3Be3,4

— nyzmi y ucex All have poods of crosses and stars...

Katt mvikrre — "H cmex H rpex"!3 "Laughable

and sinful"—as you see.

Estimates of the size of the

émigré community in Los Angeles in the early 1930s

vary between fifteen hundred and two thousand.' Most of the émigrés came to

California from the Far East, although some came from Europe and migrated from

the East to the West coast. If there was a single economic reason for going to

Los Angeles during the 1920s it was the burgeoning

film industry, which specialized in fabrication of the real. It welcomed

immigrants into its ranks, especially since many in the movie world were also

immigrants (mostly German, East European, and Russian Jews), who designed for

themselves successful American identities. The Russian Jews typically knew

Russian, and despite the history of anti-Semitism in Russia they were willing

to hire White refugees, especially those who either had a noble pedigree or

could pass as aristocrats in a community that did not know how to distinguish

authentic titles from fabricated ones.

Dislocated and in most instances

impoverished, many of the emigres succumbed to impostership,

claiming if not a more illustrious past then at least a more exotic one than

they had actually lived. Many of those who ended up in the film industry were

complicit in commodifying their Russianness and participating in the simulation

of Russian authenticity on the silver screen. This is what Alexander Woloschin satirized in the quoted passage from his memoirs

in verse, deriding the manufacture of fake identities by Hollywood Russians for

use outside the community. It is as if he did not understand that the aura of

authenticity, or simulacra of the real, was what movies were made of.

Acceptance of such a perspective, however, would have required a very different

sensibility from that of the traditional Russian community in Hollywood, which

insisted on preserving what they perceived as an authentic vision of their

homeland. Few had any appreciation of what Jean Baudrillard

would later call "simulacra" and of their replacement of

reality—certainly not among Hollywood Russians.'

Perhaps the most striking example

of the slippery relation between authentic Russian culture and its simulacra is

the provenance of the first Russian Orthodox church in

Los Angeles built in 1928. During the 1970s, someone

from the postrevolutionary emigration told me that

the Holy Virgin Cathedral on Michel Torena Street in

Los Angeles was originally built for a Hollywood movie and that the studio—the

gentleman did not remember its name—gave it to the Russian community after the

film's completion. I was intrigued by this story for years, and when Beth

Holmgren invited me to give a paper on Russians in Hollywood, I decided to

investigate it. I first asked Marina Aleksandrovna

'A. A. Voloshin, Na putiakh i pereput'iakh:

Dosugi vechernie (San

Francisco, 1953), 33.

4See, for example, George Martin Day, The

Russians in Hollywood: A Study in Culture Conflict (Los Angeles, 1934),

2-3; or Ivan K. Okuntsov, Russkaia

emigratsiia v Severnoi i luzhnoi Amerike

(Buenos Aires, 1967), 362.

'See Jean Baudrillard,

"Simulacra and Simulation," in Postmodernism: An International

Anthology, ed. Wood-Dong Kim (Seoul, 1991).

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 189

Golitsyn-Dakserhof, one of my informants who has since

passed away, but her recollection of how the church came into being was rather

vague, even though she had been a member of the parish and her mother, Princess

Liubov' Golitsyn, had

willed their family icon to it. It hangs in the church to this day, as do icons

belonging originally to other Russians associated with the film industry.

In my hunt for

more specific information, I turned to the memoirs of Sergei L'vovich Bertenson (1885-1963),

the administrator of the Moscow Art Theater and assistant to Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, who came to the United States in the 1920s together with the theater. After its highly

successful second tour in 1926-27, Nemirovich and Bertenson stayed in Hollywood in the hope of making a film

career; they even thought of establishing a Russian film studio on the model of

the Russian studio in Paris in the 1920s. Their plan

was to write "authentic" screen adaptations of Russian literary

classics, in contrast to Hollywood's standard Russian kitsch, but none of their

adaptations were filmed. I remember Sergei L'vovich

from my teenage years—when he would come and visit his relatives in Monterey,

California, where I grew up. We girls would ask him about Natalie Wood, then a

rising star, but he would quickly turn to Hollywood films about Russia from a

bygone era; he referred to them as "trash" (razvesistaia

kliukva), as did other Russians of his

generation. He never made a career in Hollywood, working instead as a prompter

in the movies for many years.'

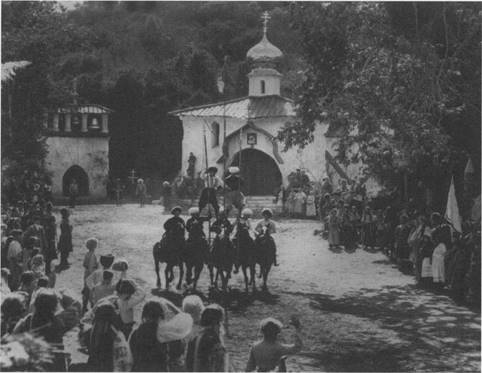

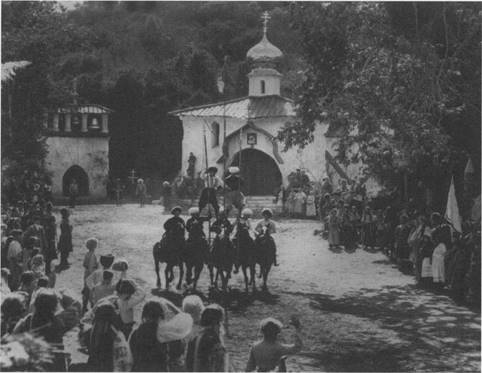

The only film about which Bertenson

had anything good to say in his memoirs was The Cossacks (1928), a loose

adaptation of Tolstoy's eponymous novel. His praise was not for the screenplay,

however, but for the set design.' He and Nemirovich-Danchenko

were taken to the set of The Cossacks where, writes Bertenson,

Russian language, songs, and balalaika music were heard everywhere. The film,

whose budget was $600,000 and was expected to cost a million, employed about

five hundred extras, among whom were twenty-seven performing Cossacks and sixty

Russians from the local community. Despite Bertenson's

contempt for Hollywood's Russian trash, he was impressed by the Cossack

village, which included a church, built on a large piece of land owned by MGM

in what is today Culver City. "The illusion of Russian scenery was so

great that it was hard to believe that you are in California," writes Bertenson, allowing himself a note of nostalgia."'

6Sergei Bertenson

was an art historian who had been involved in the conservation of old Russian monuments before joining the Moscow Art Theater.

He was the son of one of the personal physicians of Nicholas II, Lev B. Bertenson (a Russian Jew born in Odessa who converted to

Lutheranism) and of opera singer Olga A. Skalkovsky,

daughter of the well-known historian A. A. Skalkovsky.

The Bertensons were the hosts of a Petersburg salon,

attended by such famous cultural figures as Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Tchaikovsky,

Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Shaliapin, Repin, and many others. Among L. B. Bertenson's

prominent patients were Turgenev, Tolstoy, Leskov,

and Mussorgsky. Scion of a prominent medical family, he was an influential

progressive doctor, whose scholarly publications included hygienic practices in

Russia and scientific investigations of tuberculosis. Remaining in Los Angeles,

his son, using a pseudonym, wrote short articles for the Soviet press about the

West till the early 1930s. According to his grand nephew Dmitrii Arensburger, who lives in Washington, DC, he wrote these

articles in order to help support his mother in Leningrad, who would receive

his honoraria.

'Bertenson

writes about the script with dripping sarcasm. Having rejected the first

adaptation by Victor Turzhansky, Irving Thalberg suggested to him a collaboration

with one of his regular writers. Apparently this writer suggested a plot

combining The Cossacks with Gogol's Taras

Bulba and the tale of Sten'ka

Razin. See Sergei L. Bertenson,

V Khollivude s V I. Nemirovichem-Danchenko

(1926-1927), ed. K. Arensky (Monterey, CA, 1964),

134-35.

'Ibid.,

154-55.

190 Olga

Matich

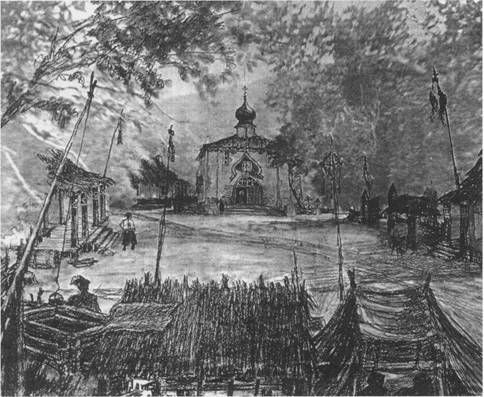

My little

treasure hunt took me next to the archive of The Cossacks located in the

Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and

the Film Library at the University of Southern California. The picture archive

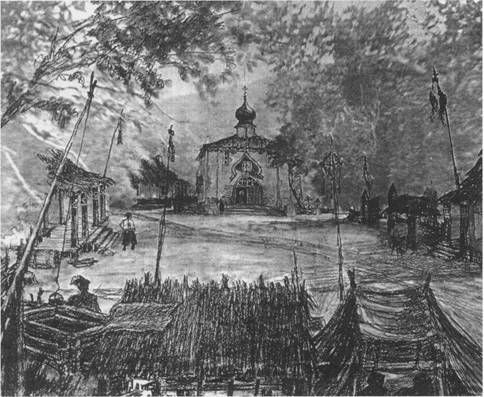

of the film revealed a sketch of a church which looked

just like the original Holy Virgin Cathedral, as did the church in the film

itself. It had been designed by the assistant art director of The Cossacks, Alexander

Toluboff (1882-1940), a highly respected member of the

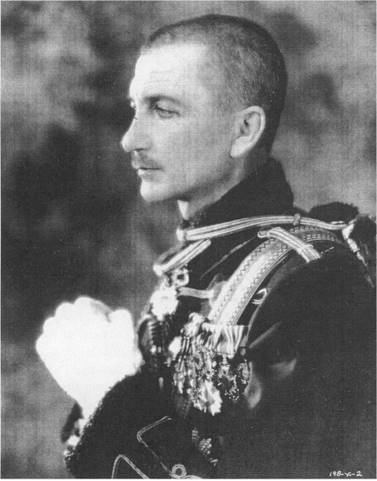

Russian community (Figs. 1 and 2).9 As I would learn later, he was

also the architect of the cathedral. The blueprints were approved by the city

on 8 February 1928, shortly after the completion of The Cossacks.rn

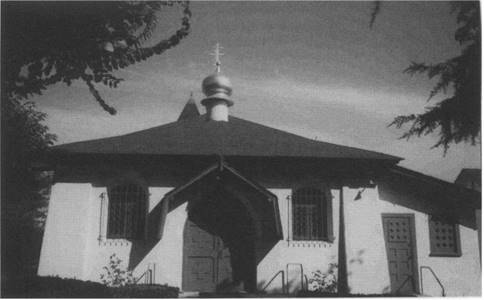

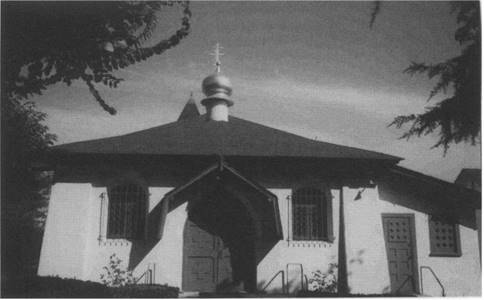

The church, expanded since 1928, still stands in

the Silver Lake area of Los Angeles (Fig. 3).

Flo. 1 Alexander Toluboff's sketch of church for The Cossacks.

This little-known

piece of Hollywood history reveals the close collaboration of the film industry

and the Russian community. The written history of the church foregrounds the

parishioners who worked in the studios and supported the church community

during

'Trained as an architect and civil engineer in St.

Petersburg, Toluboff (Tolubeev)

was the art director on the following Russian films: Love (1927), Mockery

(1928), and Rasputin and the Empress (1932). He also worked

on other films, receiving an Oscar nomination for the classic Western Stagecoach

(1939). '°The document is on record in the Los

Angeles Planning and Safety Department.

The White

Emigration Goes Hollywood 191

the Great Depression." The parish was (and is)

proud of its church in the Pskov style, the community's collective symbol of

cultural continuity, which, from the point of view of the old emigration, had

been disrupted by the Bolsheviks. The question, however, is whether the irony

of the mediating role of Hollywood in the provenance of the church had been

lost on the community. The belief of some that the church, built for a

Hollywood film, was then given to the Russian community and moved to its

current location sounds more like a Gogolian parody

of American mobility than a real foundation history. The facts, as I have been

able to reconstruct them, are that Toluboff simply

used the same design for the actual church as for The Cossacks, whose

likeness had first been built on the set.

FIG. 2 Still from The Cossacks (Personal archive of M. Protzenko).

"Among those who worked in

the studios and supported the church fmancially were M. Auer, 0. Baclanova, M. Vavich, A. Woloschin, N. Koshits, A. Kulaeva (S. Karim),

E. Leontovich and her husband G. Ratov,

N. Soussanin, A. and T. Tamirov,

L. Kinskey, I. Khmara, V. Sokolov, and others. See P. Gudkov,

"Vospominaniia V. L. Maleeva

ob osnovanii tserkovnogo prikhoda v gor. Los Anzhelose,"

in 25-tiletnii iubilei Sviato-Bogoroditskogo Khrama Ikony Bozhiei Materi

"Vzyskanie Pogibshikh"

(Los Angeles, 1953), 12-13. Mikhail Vavich

(1885-1930), the prerevolutionary king of the Russian operetta, helped purchase

the land for the church and paid for the iconostasis. Inside the church still

hang icons donated by Russians who worked in the film industry, including

Alexander Novinsky and Leonid Vasian (1900-72), a

Hollywood art director and assistant architect of the Holy Virgin Cathedral. Vavich (d. 1930) made a short-lived but successful career

in Hollywood in supporting roles, and not just of Russians. He came to

Hollywood as a leading performer in Baliev's famous

cabaret ensemble Chauve-Souris or Letuchaia mysh'. Vavich's name was closely associated with the

Russian-American Artistic Club on Harold Way and Western Avenue in Los Angeles,

which opened on 25 February 1928 with a banquet for Baliev.

It was frequented not just by Russians but also by the American Hollywood

community. Vavich sang gypsy favorites there every

Saturday, while also participating in the church choir.

192 Olga

Matich

The irony is that

Russian Hollywood accepted a house of worship whose design had been

"authenticated" by the entertainment industry. This may explain why

there are no written traces of the Hollywood origins of the church in the

annals of the émigré community, and that they remain only as part of its

unwritten history.'2

It is telling that Bertenson,

a member of the Holy Virgin parish from its inception, does not make any

references to this story, in all likelihood because the cathedral's apparent

affiliation with a movie must have been an affront to his cultural sensibility

and to his veneration of the authentic object. My guess is that Marina Aleksandrovna Golitsyn-Dakserhof's

inability to remember its origin reveals a similar instance of repression,

especially since Toluboff had been a family friend

and the patron of her brother, the future art director Alexander Golitsen (as he spelled his name in Hollywood). Yet the

church in

FIG. 3 Holy Virgin Cathedral in Los Angeles

(2001, photograph by author).

The Cossacks represented precisely the kind of authenticity that Russians like Bertenson demanded of Hollywood films about their homeland.

Even though it was a perfect replication of an original, its affiliation with

the actual church in the community—through Toluboff—had

to be repressed. My assumption is that had the sequence of events been

reversed, the fact that the same design had been used for both would have been

part of local émigré history, with the right of primogeniture going to the

community.

Not only were props used to proliferate simulated

authenticity in Hollywood, so were fake aristocratic titles. With the

dissolution of the power of the original over imitation—for reasons of

ignorance and a commercially motivated sensibility—the film industry

'Bishop Tikhon of the Holy Virgin Cathedral, an

Irish-American who converted to Russian Orthodoxy, corroborated the story

linking the church to a movie set in a private conversation in August 2000.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 193

remunerated aristocratic titles without knowing whether they

were simulated or real. F. Scott Fitzgerald writes in his unfinished novel The

Last Tycoon that the movie mogul Monroe Stahr,

based on MGM's legendary artistic director Irving Thalberg,

casts a real prince in a film about the Russian Revolution in order to assure

an "authentic feel." But can we be certain that Thalberg

could distinguish between an original and a simulacrum? We know from an example

suggested by film historian John Baxter that King Vidor apparently could not.

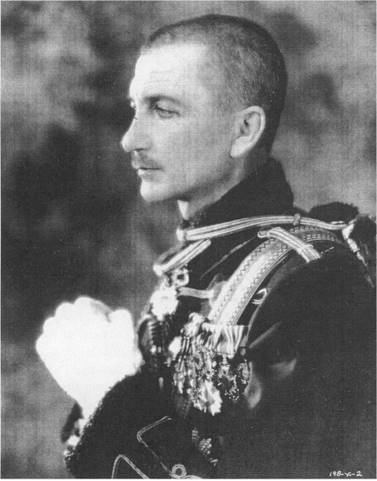

Describing King Vidor's His Hour (1924), a sumptuously filmed melodrama

about Prince Gritzko (!) and a young English

gentlewoman, Baxter writes that the director cast a "real tsarist

aristocrat" to play the role of the grand duke. He did so "to sustain

the Russian atmosphere," even though the Russian aristocrat, according to

Baxter, chose to play under a pseudonym. What both the filmmaker and scholar

seem to have missed is the ludicrous collocation of "Prince Gritzko," with the name Gritzko

coming from one of Gogol's Ukrainian tales, not from Russian high society. Moreover, King Vidor apparently mistook Michael Pleschkoff, an untitled Russian general, who played the

grand duke, for an aristocrat (Fig. 4).13

In my study of Russians in Hollywood, I learned of

two families who commodified their aristocratic titles, going to tinsel town in

the late 1920s. One was recruited by a studio

representative who came to the San Francisco area—where a large Russian community

had existed since the beginning of the twentieth century—in search of Russian

extras for films in the "Russian genre." Although this family's

titled origin seems doubtful, both parents and children went to work in the

movies as "aristocrats." The other family, the Golitsyns,

bona fide aristocrats, came to Hollywood from Moscow via Siberia, China, and

Seattle, Washington. Doctor Alexander V. Golitsyn,

son of the liberal governor-general of Moscow and himself a liberal, escaped

from Russia after the October Revolution. In Los Angeles, he became a doctor in

the Russian community. The first member of the family to get her foot in the

film industry was his younger daughter Natalia, whom Elinor Glyn (popular

author of potboilers that were made into movies) introduced to Cecil B. De

Mille, no doubt as "a Russian princess." Natalia's first bit part was

in De Mille's King of Kings (1927); her name

appeared in the cast probably because of its aristocratic cachet. Unsuccessful

in her movie career, she later married the nephew of Nicholas II, Prince Vasilii Aleksandrovich, whose

brothers had been involved in the Rasputin affair. Vasilii

was a real Romanov, unlike, for example, the owner of the famous Romanoff 's on Sunset Boulevard, Mike Romanoff.14 Born Hershel Gerguzin

(in Lithuania), he became

'3The

Prince played under the pseudonym Mike Mitchell. See John Baxter, The Hollywood Exiles (London, 1975), 134.

Neither the name Mitchell nor that of Michael Pleschkoff

appears in the cast. According to an article in an émigré newspaper, there was

a Russian bit player G. Rodionov in Hollywood who

worked under the name George Mitchell (Taisiia Bazhenova, "Russkii Los-Anzhelos," Novaia zaria, 5 January 1940). Pleschkoff

(d. 1956), son of infantry general M. M. Pleshakov,

had been a general in Russia. (I located this information only after publishing

my first article about the Russians in Hollywood, in which I questioned his

military rank.) His name appears in subsequent films in which he worked both as

bit player in Into Her Kingdom (1926, with Corinne Griffith), a fantasy

about the fate of the tsar's family after the revolution, and as technical

adviser of The Eagle (1925, adaptation of Pushkin's Dubrovsky

with Rudolph Valentino) and Resurrection (1926).

"I remember Grand Duke Vasilii's brother Nilcita Aleksandrovich Romanov, the son of Grand Duchess Ksen'ia, sister of Nicholas II, and Aleksandr

Mikhailovich Romanov, cousin of the emperor. He lived in Monterey, CA, in the 1950s, where he taught Russian to servicemen at what is now

the Defense Language Institute. His pedagogical

194 Olga

Matich

Hollywood's most successful imposter, even using the sobriquet

"Heir" sometimes, as if he were waiting to return to the throne.

Quite preposterously, he also liked to call himself Prince Michael Alexandrovitch Dmitrii Obolensky-Romanoff. One wonders how these

FIG. 4 Gen.

Michael Pleschkoff in His Hour.

sobriquets were received and if they were meant

tongue-in-cheek. What they corroborate, however, is that the world of celluloid

frequently rewarded manufactured identities and simulated authenticity with

greater financial success than it did authentic names and

skills were nil, but the soldiers and

officers liked him. After all, he was the nephew of the last tsar, and he would

tell them stories about his youth and show them his

box of family treasures and jewels. He also taught the soldiers

skills were nil, but the soldiers and

officers liked him. After all, he was the nephew of the last tsar, and he would

tell them stories about his youth and show them his

box of family treasures and jewels. He also taught the soldiers

Russian swear words. In the

early 1960s Nikita Aleksandrovich

lost his teaching job because he refused to take U.S. citizenship, which would

have resulted in the official loss of his royal title. He and his wife moved to

a Russian convent in Calistoga, CA, living there on welfare until Queen

Elizabeth of England learned about her relative's predicament and invited him

to live in Buckingham palace, or so I remember the last part of the story,

which may be a legend. The rest is accurate.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 195

ranks. Despite its fascination with impoverished

aristocrats, Hollywood privileged the traditional "American dream" of

"from rags to riches" over dispossession and tragedy.

The older Golitsyn

daughter Marina (Marina Aleksandrovna Dakserhof), whom I met a few years ago while working on the

Russian community in Hollywood, earned some money as an extra too; this was

preferable to her job in Seattle where she had worked in a suitcase factory and

department store. As she told me, she was hired to appear in Clarence Brown's Anna

Karenina (1936) for her good manners and knowledge of ballroom dancing;

because she had her own evening dress for the part—made by her mother—she

received an extra five dollars per day, fifteen in total. Leonid Kinskey, one of the few successful Russian actors in

Hollywood, called this category of players "dress extras." They

"had full dress, dinner jackets. They were getting more money." When

asked about Hollywood's Russian community, Kinskey

tellingly mentioned only its aristocrats, adding that the only convertible

currency they had was "manners and good clothes.""

According to the sociologist George Martin Day,

who knew the Russian community in Los Angeles well, Princess Golitsyn (née Trubetskoy) had a

dress shop in Hollywood that specialized in fine embroidery.'6

Her younger son Alexander would later make a major career as art director, becoming

head of the art department at Universal in the 1950s

and winning three academy awards—for Phantom of the Opera (1943), Spartacus

(1960), and To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)." As I mentioned

earlier, he got his start in the movies under the tutelage of Alexander Toluboff, the first successful Russian art director in

Hollywood.

So the film

industry did remunerate people of high rank, especially if they were linked to

the Romanov family or to events associated with the Revolution, preferably

both, as in Last Command (the general is also cousin to the last tsar).

The best-known Russian in Hollywood during the late 1920s

and first half of the 1930s was Gen. Fedor Lodyzhensky, Hollywood's

ubiquitous Russian general, first discovered by Gloria Swanson. Apparently he

tried to convince her to "make a picture based on the Women's Battalion of

Death," which defended the Winter Palace in October 1917.18

According to silent film historian Kevin

Brownlow, Lodyzhensky—"for a while a penniless

film extra"—was the prototype for the tragic hero of Sternberg's film.°

Sternberg claims in his memoirs that he had been part of what he called his

"émigré Duma," an advisory council on films in the Russian genre. An

"expert on borscht," Lodyzhensky was also

the owner of the fashionable Double Eagle on Sunset and Doheny in Beverly

"Yuri Tsivian,

"Leonid Kinskey, the Hollywood Foreigner," Film

History 11 (1999): 180.

"Day, Russians in

Hollywood, 38.

"For an oral history of Alexander Golitsen see the film archive of the Margaret Herrick

Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Los Angeles.

'8General

Lodijensky and Dorothy Famum,

"The Cossacks" (Treatment), 24 July 1926, p. 4. Unpublished document in Margaret Herrick Library of Academy of

Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Two women's infantry battalions and

several smaller detachments consisting of women were formed after the February

Revolution. They came to be known as "battalions of death" and were

among the troops that defended the Provisional Government in October. Some of

the women joined the White Army after the Bolshevik Revolution.

"Kevin Brownlow, The

Parade's Gone By (Berkeley, 1968), 196.

196 Olga Matich

Hills for a few years, frequented by such stars as Greta Garbo and

John Barrymore, who consumed its famous beetroot soup. A charming

man-about-town and respected member of the émigré community, he had been the

owner and manager of several Russian restaurants in New York and Hollywood, his

other source of income.

Predictably, one

of Lodyzhensky's background papers for The

Cossacks (1928)—not Last Command—on which he worked as technical

adviser, was a memorandum, entitled "A few real facts of the private life

of the Imperial Family of Russia." Instead of offering relevant background

information for the film, the essay relates the general's intimate affiliation

with the Romanov family, especially with the young heir, while serving in the

Imperial Horse Guard at the beginning of the century.2°

Proximity to the tsar was the stuff of the most prized Russian Hollywood

legends! Lodyzhensky clearly understood its symbolic

capital.

What is

interesting in his case is that he may not have been a general at all. This was

Marina Aleksandrovna's comment to me, but only after

I became a trusted émigré insider (svoia). Initially,

she corroborated the information I gleaned from Hollywood sources—that he had

been a general in Russia. In other words, Marina Aleksandrovna

when discussing his background with me at first played along with the new

social hierarchies, in which simulacra had "conquered the real,"

revealing the émigrés' double standard: solidarity with the imposters against

the new world, and preservation of old world hierarchies inside the community.

So Lodyzhensky, also known as Theodore Lodi, may have

invented his rank in tailoring a career to the studios' specifications, which

gave preference to a Russian biography that combined aristocratic origin and

proximity to the court.

The irony of Last

Command, the best film in the Russian genre, is that it cast real Russian

generals as extras, while the main role of the former general and Romanov

prince was played by a German actor.2' We

learn from Sternberg's memoir that he authenticated Last Command by

hiring high-ranking White émigrés, who comprised his "Duma," to work

in the film:

mAccording to George Day, Lodyzhensky was a colonel in

the Russian division in France in 1918 and acquired the rank of general after

leaving for the United States [!]. A risk-taker and wheeler-dealer, Lodyzhensky exhibited "courage, bluff, and

adventure" in charting his upward mobility in the United States (Russians

in Hollywood, 2023). The film career of Fedor Lodyzhensky included bit parts in Her Love Story (starring

Gloria Swanson, 1924), The Swan (1925), Into Her Kingdom (1926), They

Had to See Paris (1929), Once a Sinner, General Crack (1930), Ambassador

Bill (1931), Down to Earth (1932), Tambour Quest (1934), and Man

Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo (1935). Under the name of Theodore Lodi,

he served as the technical adviser on Rasputin and the Empress (1932), a

star vehicle for the three Barrymores (John, Ethel,

and Lionel), directed by Richard Boleslawski.

Together with art director Alexander Toluboff, Lodyzhensky helped reproduce the palace interiors from

details supplied by photographs. He was also the film's drillmaster. Dorothy

Jane Ferguson claims that he was a "famous architect of the Czarist

regime," confusing him with Toluboff, as well as

"former commander of the Czar's bodyguard" ("Rasputin and the

Empress: The Story of the Film," Rasputin and the Empress [MGM

pamphlet]).

211928 was

an important year in Hollywood's "Russian production." Besides Last

Command, the studios brought out The Patriot (dir. Ernst Lubitsch), The

Cossacks, The Mysterious Lady (an MGM vehicle for Greta Garbo), Scarlet

Lady, Red Dance, and Clothes Make the Woman (a Last Command spin-off).

The Patriot, in which Janning plays the mad

Emperor Paul, is considered by some his best role, but unfortunately it has

been lost, although some of the mass scenes apparently were used later by

Sternberg in the Scarlet Empress, with Marlene Dietrich as Catherine the

Great.

The White

Emigration Goes Hollywood 197

I fortified my

image of the Russian Revolution by including in my cast of extra players an

assortment of Russian ex-admirals and generals, a dozen Cossacks, and two

former members of the Duma, all victims of the Bolsheviks, and, in particular,

an expert on borscht by the name of Koblianski. These

men, especially one Cossack general who insisted on keeping my car spotless,

viewed Jannings's effort to be Russian with such

disdain that I had to order them to conceal it, whereas Jannings

openly showed his contempt for their effort to be Russian on every occasion.22

Sternberg

exaggerated the numbers: Alexander Novinsky, known as ex-admiral (see below),

was not in the film, nor was Lodyzhensky, the real

expert on borscht; writing

about these men many years later, Sternberg confused

Nicholas Kobliansky, the former

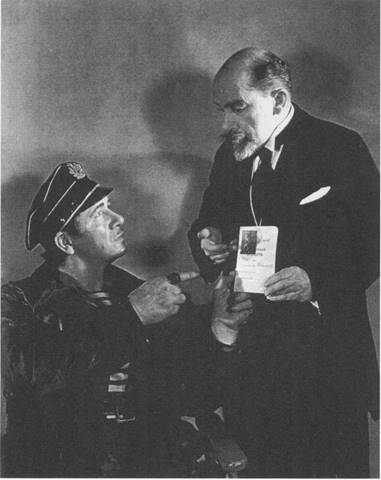

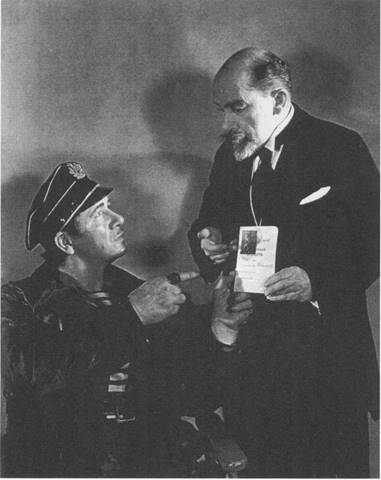

FIG. 5 Gen. Alexander Ikonnikoff

(right) with Emil Jannings in Last Command.

member of the State Duma and the film's technical adviser,

with Lodyzhensky. The two real high-ranking officers

that I was able to identify in the film were infantry general Alexander Ikonnikoff (1884-1936), who fought in Kolchak's army in the

Far East (Fig. 5), and Gen. Viacheslav Savitsky, minister of defense in the free Kuban government

"Josef von Sternberg, Fun

in a Chinese Laundry (San Francisco, 1965), 132.

198 Olga

Matich

(Kuban Rada) in

1918.23 It was Savitsky who kept Sternberg's

car immaculately clean, reinforcing the image of the émigré's downward

mobility.

The question that

arises in this context is whether Sternberg's advisory Duma influenced the

content of Last Command, a film not only about the loss of home and

country but also about the making of a film that showed both the excesses of

imperial power and the trauma of emigration. Most likely, Russian advisers had

an impact on the film, since it ultimately offers a sympathetic, not to say

sentimental, representation of the general. If one believes a Russian reviewer

of the film, it even evokes real historical events, such as the scene in which

the general and his staff are dragged off a train by a revolutionary mob to be

summarily executed. This, according to the reviewer of the émigré newspaper Novoe russkoe slovo, refers to the murder of Gen. Nikolai Dukhonin, the last supreme commander of the army before the

October Revolution: a mob killed him at the railway station in Mogilev?' But

this was the kind of emotion-packed ideological subtext accessible only to

Russian viewers and without resonance for the regular movie-going public.

The studios made use of the high-ranking military

men not only as extras and consultants but also in the publicity campaigns of

its Russian production about the Revolution. One of Paramount's publicity

photos for Last Command shows General Savitsky

in his uniform with the female star Evelyn Brent. The caption reads: "Viacheslav Savitsky, who once

ruled with whip and sword as Kuban Cossack general, is now a private in the

ranks of Hollywood 'bit' players and is at the beck and call of assistant

directors in the film center" (Fig. 6). The implication is that Last

Command was based on the story of Savitsky, which

lent historical authenticity to the film; it also underscored, unwittingly, the

irony of real generals being replaced by actors. Equally ironic is the fact

that Savitsky had not fought "with whip and

sword" during the Civil War. As defense minister of the Kuban government,

he went to Paris in 1919 as part of a Russian delegation and did not return

home.

The caption further reads that the co-star of the

film, Evelyn Brent, "is shown admiring one of the former Russian leader's

medals." The medal is a Cross of St. George, a decoration for bravery,

which was the most revered military symbol of the White emigration. In regard

to the other Russian general in the film—Ikonnikoff—Emil

Jannings told the New York Times that he wore

his Cross of St. George on the set all the time." I know of its sentimental

value from personal experience, because my father, who ended up in the

23Among

General Ikonnikoff's other uncredited bit parts were Into

Her Kingdom, The Volga Boatman, Four Sons (all 1926), The World and the

Flesh, The Man Who Played God (both 1932), Lives of a Bengal Tiger (1935),

The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo (1935), and Cain and Mabel (1936).

He played mostly Russians. In 1918, Viacheslav Savitsky was promoted to the rank of colonel and just a few

months later to major general. Among other films in which he had uncredited bit

parts were Mockery, Love (both 1927), The Awakening (1928), The

Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo (1935), Cain and Mabel (1936),

The Soldier and the Lady (1937), Balalaika, and Hotel Imperial

(1939).

24V. Krymskii, "Russkii Khollivud na ekrane,"

Novoe russkoe slovo, 24 January 1928. There seems to be a geographical

correspondence as well: Dukhonin was killed in

Mogilev, a city in Belarus with a large Jewish population then. The town in

Stemberg's film also resembles a Belarus or Ukrainian town with a large Jewish

population.

""Jannings and

'Extras,"' New York Times, 6 November 1927.

The White

Emigration Goes Hollywood 199

White Army as a

thirteen-year-old, received this decoration; it became

a fetish object for him, even though he was not a military man. As a child, I

would often ask him to tell me the tale of his spying mission and imprisonment

by the Bolsheviks, for which he received the decoration, in lieu of a more

conventional bedtime story.26

The Last

Command has a nostalgic scene, very likely suggested by a member of

Sternberg's "Duma," in which the general takes the Cross of St.

George from his wallet and pins it to his studio uniform. The gesture takes him

back to the front during the First World War and allows him to reinhabit his prerevolutionary past (Fig. 7). Invoking the

medal scene in the film, the publicity photo with Savitsky

suggests its migration from his Cossack chest to that of Jannings.

It authenticates the scene in the film by commodifying Savitsky's

prized fetish of his Russian past.

FIG. 6 Gen. Viacheslav Savitsky with Evelyn Prent (publicity photo for Last Command).

Paramount made use of the military past of the

Russian extras once again to promote The World and the Flesh (1932), a

film about the Russian Civil War. A widely used publicity photo was that of

Alexander Novinsky, the former port commander of Feodosiia,

showing his tsarist naval passport to the star of the film, George Bankroft, who plays a Bolshevik sailor (Fig. 8). The

caption follows the same plot line as the one representing Savitsky's

past history: "Loses admiralty, becomes movie bit

player. Alexander Novinsky,

26Boris Pavlov, Pervye chetyrnadsat' let (Posviashchaetsia

pamiati Alekseevtsev), ed.

Olga Matich (Moscow, 1997), 50-60.

200 Olga Matich

one-time commander of the Imperial Russian Navy who was

slated to become an admiral lost his all in the revolution and is now a small

part player in the movies in Hollywood." The underlying paradigm—the

reverse of the Hollywood plot of from rags to riches—celebrates the trauma of

social ruin, thematized in the fictionalized

biography of the general in Last Command and the true story of General Savitsky in the publicity photo. Unlike the biographies of

other military men who populated Hollywood's Russian genre, the story of

Novinsky has an additional literary twist. In his previous life, he had known Osip Mandelshtam and Maksimil'ian Voloshin in the

Crimea, serving as the prototype of

FIG. 7 Emil Jannings as commander-in-chief on the front.

one of Mandelshtam's

characters in Feodosiia.27 In the

story "Harbor Master" ("Nachal'nik

porta"), which forms part of Feodosiia,

the unnamed Novinsky, a self-confident naval

27See Osip Mandershtam,

"Nacharnik porta," in Feodosiia,

1925. For further discussion of

Novinsky's biography, see Matich, "Russkie v Gollivude," 422-23, nn. 1, 2.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 201

officer, gives the homeless poet a place to sleep in Wrangel's Crimea. Little did Mandelshtam

know that the harbor master would become a lowly film extra in Hollywood.

The dispossessed tsarist refugee became a staple

ingredient of Hollywood's immigrant narrative. Acquaintance with one of them

legitimized the directors, screen writers, and actors working in the Russian genre.

Jannings, for instance, who maintained that he had

FIG. 8 Alexander Novinsky (left) with George

Bancroft (publicity photo for The World and the Flesh).

suggested the plot of Last Command to Paramount,

claimed that the idea came to him after having observed the pathos of the

émigrés' lived experience. In his memoirs, he tells the archetypal anecdote of

having befriended a former tsarist officer who broke down on the set of Last

Command one day because Jannings was reenacting

his life." This

"Emil Jannings

claims that he helped the former officer become a Russian consultant in

Hollywood. See his Theater, Fim—das Leben and ich (Berchtesgaden,

1951), 185-87. The screen play of Last Command was credited

202 Olga Matich

sentimental tale of the dispossessed Russian who recognizes

himself in the fake general is the kind of authentication that Hollywood

thrived on.29

Most of the

extras, bit players, and consultants on Russian films left their homeland with

the White Army or some special Cossack detachment—as professional military men

or volunteers fighting against the Bolsheviks in the Civil War. Needless to

say, most of them had no prior experience in the entertainment industry. Since

many of then did not have professions that could be

readily converted into gainful employment in the new world, they preferred

working in the movies to pursuing lives as cabdrivers or doormen,

tailors or shoemakers. Though inconsistent, the pay was

good, ranging from five to fifteen dollars a day; between films, they would

return to their newly acquired mundane professions.

There were other instances of accidental careers

in the movies besides those of Russians with genuine or claimed titles and

genuine or faked military experience. A typical example is the story of a

Russian railway worker who "quite by accident became an architect in the

movies and decorates films set in Europe and especially Russia."3°

A better-known case was the career of the former

member of the State Duma Nikolai Kobliansky (who

apparently had some theatrical experience in Petersburg). Kobliansky

became a relatively successful technical adviser on Russian films, including Last

Command. The Los Angeles Times in 1932 called him "a Hollywood

fixture—an approved authority on matters Russian":

Remembering and

helping to relive the most tragic period of his life is a paying business for

Nicholas Kobliansky. Hollywood is paying him

dividends on the loss of his property, his friends and his worldly position.

His knowledge of Russia, its manners and customs, and particularly of the

period just before and after the revolution, has been sought by motion picture

producers ever since he first entered the film colony some six years ago.31

There may have

been yet another reason that attraced these émigré

men and women to the film industry, however. Russian subject matter, no matter

how inauthentic, helped fuel émigré nostalgia and dreams of return. What united

émigré communities in the first decade everywhere was the belief that Soviet

rule was temporary and that they would

soon be able to go home. In the interim, they would

convert what they perceived as a

to Lajos Biro, even though Sternberg claimed that it was

his and that it was based on an anecdote told him by Lubitsch. Jannings was one of the great German actors of his time,

best known in the United States for his role in Stemberg's Blue Angel.

to Lajos Biro, even though Sternberg claimed that it was

his and that it was based on an anecdote told him by Lubitsch. Jannings was one of the great German actors of his time,

best known in the United States for his role in Stemberg's Blue Angel.

29For a

thorough discussion of the film itself see Matich, "Russkie

v Gollivude," 411-16.

30Olcuntsov, Russkaia emigratsiia, 362.

'Russian in Hollywood as

Adviser," Los Angeles Times, 19 June 1932. Jannings

spoke of Kobliansky with respect, telling a New

York Times correspondent in 1927 that he had also been a member of the Art

Committee of the Imperial Theatres in Petersburg, producing several operas and

ballets ("Jannings and 'Extras'"). Besides Last

Command, Kobliansky worked as technical adviser

in Duchess in Buffalo (a popular farce of 1926 with the famous Constance

Talmadge as American dancer in Russia who falls in love with a grand duke), Resurrection

(1927), Dishonored (Sternberg, 1931), The Patriot (1928), and

Song of the Flame (1930). During World War II and right after, he played

in Mission to Moscow (1943) and Northwest Outpost (1947). So even

though Lodyzhensky was a more colorful figure, Kobliansky was a more stable presence in Hollywood's

Russian production.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 203

national tragedy

into a cultural mission whose primary goal was the preservation in exile of

prerevolutionary values and to a lesser extent proselytism of the

"true" meaning of Russian history and culture to

"foreigners." They turned their experience of exile and traumatic

loss into a newly found mission.

Needless to say, most extras had little influence

on the Russian films in which they worked, frequently knowing neither plot nor

subject matter. This is thematized in Last

Command, where the former general is summoned to the studio without being

told anything about the film. Nabokov, who had worked as an extra in Berlin,

refers to the same in his first novel Mary (Mashenrka):

while watching such a film, Ganin remembers with

shame that a "whole regiment of Russians was rounded up in a huge

barn" and filmed without knowing the plot.32

A film about the making of a film, Last Command also represents the

disdain to which the émigrés are subjected in the new world, rendered by the

figure of the American assistant director. As he prepares the general for his

"last command," he insists on knowing Russian military dress better

than him because he had already made twenty Russian pictures. The ignorance of

the cocky assistant is exposed in a dramatic scene, which must have soothed

many a Russian military man's pride regarding military regalia.

Most Hollywood

films about the revolution were considerably less "authentic" than Last

Command. Poor and dependent on the studios, the émigrés usually ended up

commodifying their personal memories and cultural identities in ways that

corresponded to Hollywood's stereotypes. Russia was typically represented as a

land of luxury, characterized by golden cupolas and art nouveau decor and

populated by decadent aristocrats, on the one hand, and wild and wooly

Cossacks, passionate gypsies, and exotic Tatars, on the other." The images

infuriated émigré movie-goers, who would express disdain for Hollywood's

Russian production:

There is a

downpour of "pictures" of Russian content as if from a horn of

plenty, with one more shameless and ignorant than the next in the way they

represent our customs, culture, and society. There is no one to raise an

authoritative voice in defense of our history, literature, civilization—no one

has the resolve—and these films are made not only with the participation of

many ... Russians, but also under the supervision of Russian consultants. And

what can we expect from the hungry Russian refugees when I. L. Tolstoy—a

cynical bon vivant who has forgotten kin and homeland—is helping American

directors butcher even the works of his great father.34

Ilya Tolstoy, who looked like his father, appeared

in Edwin Carewe's Hollywood version of Resurrection

(United Artists, 1927), in which he plays the writer as cobbler cum prophet.

He also collaborated on the film script of the mercilessly butchered adaptation

of Anna Karenina—Love (MGM, 1927), with Greta Garbo and John Gilbert—the

same year." Many in the Russian community were outraged by his willingness

to commodify

"V. V. Nabokov, Sobranie sochinenii russkogo perioda v 5-ti tomakh (St. Petersburg,

2001), 2:60. 33Oksana Bulgakowa examines Hollywood stereotyping of Russia in this

issue.

"A. A. Morskoi,

"Moda na `russkoe,'" Illiustrirovannaia

Rossiia 5 (February 1929): 15.

"The script of Resurrection

was written by Frances Marion, then the best-paid writer in Hollywood,

although she claims that she protested, telling Thalberg

that she "couldn't face the ordeal of distorting another Tolstoy" (Cari

204 Olga Matich

his familial identity. The film opens with a scene in which

Tolstoy is repairing boots; in each new episode, he hammers in yet another

nail.

Although most

Russians worked in the studios for financial reasons, I believe that life on

and behind the silver screen also served a nostalgic function in their humdrum

lives. Hollywood's Russian kitsch was for many White émigrés a connection to

their homeland. After all, the émigrés had created their own nostalgic Russian

kitsch, consisting of sentimental images of birch trees, church cupolas, and

colorful Cossacks, images that differed but little from those in the movies.

And on occasion, as in Last Command, the movies offered them the

opportunity to leave cinematic traces of what they perceived as Russian

authenticity.

One of the most striking instances of adaptation

to the new socioeconomic circumstances in emigration was the transformation of

former Cossack warriors into performers of their ethnic identity. Considered

fiercely independent and proud, yet they willingly commodified Cossack rituals

in concerts, movies, circuses, and rodeo in order to avoid working in factories

and other urban occupations. Known for their riding skills, the men felt more

at home in work linked to their horses, if not in actuality then symbolically.

Their dances were typically choreographed scenes of daredevil riding in battle

and exhibition of male prowess. Older readers of the Russian Review may

remember the various Cossack troupes that still toured the United States in the

1960s, performing their exotic identities for

Americans and nostalgic songs and dances for émigrés.

Adaptations of

Tolstoy's novels were in the Hollywood air in 1926. MGM finally decided to film

The Cossacks around the same time as Last Command, and to bring

real Cossacks from Europe for what it called "its most extravagant

undertaking" that year. In contrast to Last Command, however, the

final product was a real instance of razvesistaia

kliukva. The first director of the film, Viktor Turzhansky, quit in disgust. General Lodyzhensky,

the film's technical adviser—working under the pseudonym Theodore Lodi—wrote

one of the many treatments of the film. Preposterously, he located The

Cossacks in the Civil War, with the apparent purpose of making it a film

about the struggle of what he calls the "Russian nation" against the

Bolsheviks. Using the history of the Cossacks as peasant migrants to the

southern borderlands, he interpreted the formation of the White Army as a

"migration" of "the Soul of Holy Russia, leaving its sick

body" in order to fight the Bolsheviks! "It is for us, who work on The

Cossacks," writes Lodyzhensky, "to

interpret the spiritual meaning of this migration and to glorify it."36 This was certainly a fanciful

interpretation of the Civil War in the South of European Russia. Its subtext

seems to have been anti-Semitic, suggesting that the Bolsheviks—in whose upper

ranks were many Jews—were interlopers in the Orthodox nation who

"infected" it from the outside. Needless to say, Lodyzhensky's

version was also a thorough misrepresentation of Tolstoy's novel and an

instance of an émigré effort to inscribe the White cause into Hollywood films

wherever possible.

Beauchamp, Without Lying Down:

Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood [Berkeley, 1997],

218). She had just worked on MGMs Love

(1927), the silent adaptation of Anna Karenina.

Beauchamp, Without Lying Down:

Frances Marion and the Powerful Women of Early Hollywood [Berkeley, 1997],

218). She had just worked on MGMs Love

(1927), the silent adaptation of Anna Karenina.

"Lodijensky

and Farnum, "The Cossacks" (Treatment),

1.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 205

The final version of the film was set in the

seventeenth century, conflating Tolstoy's novel and Gogol's Taras

Bulba. Represented as a time of Imperial conquest

in the Caucasus, it thematizes the conflict between

the Cossacks and Turks: a prince is sent to a Cossack village in the Caucasus

to implement the Russian policy of "blending the blood of all the peoples

of the empire" (direct quote from intertitle). He intends to accomplish

this by marrying a Cossack woman. Miscegenation in a paternalistic sense was

certainly neither Tolstoy's nor Gogol's concern. It was also never Russian

policy, Muscovite or Imperial, not to speak of the fact that the colonization

of the Caucasus had not yet begun in the seventeenth century or that the film

was really in the genre of a Western."

FIG. 9 Sergei Protzenko on the

set of The Cossacks (Personal archive of M. Protzenko).

In

prerevolutionary Russia, a Cossack joining the Imperial Cavalry was supposed to

provide his own horse and uniform. The Cossacks coming to work at MGM were to

be paid $100,000; like in the Russian army, they were also expected to provide

horses and costumes." The studio imported them from a troupe organized in

France by the notorious White Army Cossack general and anti-Semite Andrei Shkuro in 1925, whose "wolf-pack" had wreaked

havoc in the territories it occupied during the Civil War. One hundred ten

3.7For further

examination of The Cossacks see Matich ("Russkie

v Gollivude," 416-21); and Oksana Bulgakowa's article in this issue.

38Contract

from MGM signed 22 March 1926.

206 Olga Matich

Cossacks and

their families arrived in New York on 12 May 1926 under the leadership of

Alexander Melikhov and Sergei Protzenko

(1894-1984), born in the Kuban region

(Fig. 9). The son of Sergei, Mike Protzenko,

told me that his father graduated from the Imperial Cavalry School in

Petersburg, joining the Kuban Cossack forces fighting against the Red Army

during the Civil War; he participated in the harrowing Ice March, of which he

was one of the decorated survivors." After leaving Russia in 1920, Protzenko settled in Bulgaria where he organized a small

Kuban Cossack djigit troupe that

initially performed in the Balkans. The djigits

were truly astounding equestrians, exhibiting their riding prowess in

dangerous stunts, which would become the envy of cowboys and stunt men in

Hollywood; they would typically form the core of any performing Cossack troupe.

In 1925, General Shkuro invited Protzenko's

ensemble to Paris to participate in a large troupe, which toured France,

England, and Scotland. After the end of his riding career in film and rodeo,

Mr. Protzenko became a furniture upholsterer in the

studios, never having learned English very well and never having adapted to the

American way of life.

The first

American appearance of Protzenko's Cossacks was in

Madison Square Garden in 1926. This photograph of a group of exotic horsemen

riding down Fifth Avenue was reproduced many times over in newspapers in the

state of New York that year (Fig. 10). The press would refer to Melikhov and Protzenko as counts,

even though the social structure of the Cossacks did not have an aristocracy,

revealing once more the American desire to ascribe aristocracy to all Russians

who emigrated after the October Revolution. The subtext seems to suggest a

kitschy view of the Revolution—one that pitted the nation against the

aristocrats! In any case, we must assume that the capital value of the Cossacks

went up when aristocratic titles were added to their wild and wooly images.

Their performances and rowdy behavior were widely reported in the press, and

quite predictably they were linked to their historic role in defending the

oppressive tsarist regime. One article described a group of Cossacks and

members of the Russian royal family, supposedly working as janitors and

restaurant managers, walking hand in hand down Broadway!4°

What this story and others like it reflect is the public's simultaneous

fascination with royalty, and the stereotype that ascribed barbaric behavior to

the Russian ruling elite.

Whatever we may

think about their politics, it is ironic that after fighting in a brutal civil

war these Cossacks ended up abroad in the entertainment industry, staging their

identity and past military exploits to foreign audiences. One wonders how they

mediated a nostalgic recreation of the past in these performances with the

inevitable sense of its trivialization in the movies, stadiums, and circus

arenas. Like Sternberg, who comments on the disdain the Russians expressed for Jannings's effort to appear Russian in Last Command, a

correspondent of Novoe russkoe

slovo writes that the Cossacks voiced their

contempt for John Gilbert and other fake Cossacks on the set of the eponymous

film.

"I met Mike Protzenko through William Anoukichine,

also the son of one of the Cossacks who came to the United States under MGM

contract. However, he never made it to Hollywood. His two sons, having learned

that we were going to show The Cossacks (available only in film

archives) at the University of California, Berkeley,

came a considerable distance to see it. "Gazette (Niagara

Falls), 1 June 1926.

The White

Emigration Goes Hollywood 207

They would make fun in Russian of the way they

looked in their costumes and make-up.4' Their sense of superiority must have been particularly strong in those

instances when they worked as substitutes for the stars in scenes requiring

physical agility and stunt work.42

FIG. 10 Cossacks on Fifth Avenue in New York in 1926

(Personal archive of M. Protzenko).

In one of the scenes in The Cossacks a djigit rides across the screen displaying the sign of

the kukish, an extended clenched fist

with thumb between index and middle fingers. Most likely, the obscene gesture

was unfamiliar both to the American filmmakers and to American audiences. It is

certainly authentic, but what was its narrative function? Undoubtedly suggested

by the Russians on the set, it may have been intended as an in-joke reflecting

either contempt for the bowdlerized adaptation of a classic or of the Cossacks'

contempt for the filmmakers' view of their history. In other words, the gesture

represented the ambivalence of the Hollywood Russians in regard to their

commodification, expressing disdain for the new world by means of a secret code

familiar only to the in-group.

Perhaps the most

striking instance of staged Cossack identity that I encountered was the home of

Mike Protzenko, located in a working-class

neighborhood of Burbank,

G, "Kazaki v `Kazakalch,'" Novoe russkoe slovo, 6 February 1928.

"For a discussion of Protzenko's

Cossacks in the movies see the memoirs of Garvriil Solodukhin, Zhizn' i sud'ba odnogo

kazaka (New York, 1962), 88-93. Solodukhin was one of the djigit

riders in the troupe.

208 Olga Matich

California. Born

in this country, Mike knows very little Russian; his father, who married his

American wife (a passionate anti-Communist) late in life, died when he was very

young. Yet Mike is very proud of his Cossack heritage, artifacts of which

decorate his otherwise typical American home, including a painted reproduction

of the Zaporozhian Cossacks Write a Letter

to the Turkish Sultan. (Repin's well-known

theatrical painting served as a visual subtext for one of the key scenes in the

film.) There are photos and paintings of Sergei Protzenko,

as well as of Mike dressed in a beautifully tailored Kuban Cossack costume,

specially made for him by a seamstress affiliated with the descendants of the

Cossack community in New Jersey. Mike has maintained his father's archive,

containing press clippings and other items documenting Protzenko's

and his troupe's tours, in perfect condition.'"

The emigres'

complicity in the studios' commodification of Russianness and high-ranking

identity, whether real or fabricated, did not exclude self-irony. An instance

of such off-screen self-awareness was the comic opera Borshch

i kasha, staged in 1940 in the Russian community

of Los Angeles. It was a parody of the American view of Russia, inspired

directly by Balalaika (1939), an Oscar-winning musical comedy about the

Revolution from the previous season. Replete with the conventional stereotyping

of Russianness, the film featured the popular Nelson Eddy as a Russian prince

masquerading as a member of the working class. Borshch

i kasha was a benefit performance for the Holy

Virgin Cathedral; it was written and staged by the singer Aleksei

N. Cherkassky, who worked in Hollywood. The

best-known performers in the play were Nina P. Koshits,

famed opera singer, who played "Princess Kasha" (or Mme Kroshets-Farshmak), and Misha

Auer, well-established Hollywood actor, as Count Shish Kebab (Shashlyk) or Pitsio Intsa (reference to the leading bass Ezio

Pinza at the Met). The author of Borshch i kasha was both "Prince Borshch"

and Elson Non-Eddy.44 The

performance—strictly in-house—was also a self-parody. Subversive of the

community's bread and butter, the play offered an ironic vision of its

complicity in the production of Russian commercial trash for American

consumption.

"As Sternberg writes in his

memoirs, there were real Cossacks in Last Command. In all likelihood, they came from

a performing troupe organized by General Savitsky in

Paris in 1926, which, like Protzenko's, later toured

the United States. Savitsky's performers were also

from the original ensemble of General Shkuro, which

split up into factions after their tour in Great Britain, with Protzenko and Savitsky bringing

separate troupes to the United States—in the same year! As I learned from Mike Protzenko, his father and Savitsky

remained friends in Los Angeles, despite the competition between their

ensembles. It appears that there was a big demand for performing Cossacks in

the United States, of which Zharoff's Don Cossacks

were the best known. The Cossacks in Last Command did not entertain, however;

instead they performed their historical role—of putting down a revolutionary

demonstration.

"B az h en o v a ,

"Russkii

Los-Anzhelos." Besides the well-known or already

mentioned M. Auer, A. Golitsen, L. Kinskey, N. Kobliansky,

"Admiral" A. Novinsky, Ruben Mamulian, A. Savitsky, Akim Tamirov, I. Tolstoy, A. Toluboff,

and Maria Uspensky, Bazhenova

lists the following names of Russians in Los Angeles working in the studios: I.

Anatarova, A. Cherkassky,

A. Davydov (who had been a lieutenant colonel in the

Russian army and a military attaché), V. Dubinsky, N. Gay (Ge, grand nephew of the painter Nikolai Ge), I. Gest, V. Gontsov, N. Khriapin, V. Konovalova, G. Leonov, Meleshev, G. Mitchell (V. Rodionov),

Orshansky, L. Raab, Seleznev (Sila), B. and F. Shaliapin (sons of the singer; Feodor performed in

Hollywood movies until recently, [for example, in Moonstruck, 1987], A.

Shubert, and V. and L. Usachevsky.

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood 209

The only Russian

actor in Hollywood whom I met personally was Leonid Kinskey

(1903-98), a staple guest in the Beverly Hills home of a wealthy American woman

connected with the film industry. It was during the 1980s,

and Kinskey—long retired from the movies—continued

rehearsing his role as "Hollywood Russian" for the locals, especially

that of Sasha the waiter who kisses Bogey in Casablanca. Kinskey first became known in bit roles as a generic East

European radical—first in Lubitsch's Trouble in Paradise (1932) and then

in the Marx Brothers' Duck Soup (1933). In 1990, Yuri Tsivian and I interviewed him in his home; the text has

been published in Film History." Just as charming as his film

persona, Kinskey would shift from English to Russian

and back. Nearing ninety, he was living with his much younger wife in a modest

home in North Hollywood.

He told Tsivian and me

that it was his invention to kiss Humphrey Bogart in the now famous nightclub

scene. I did not ask him then whether this was an unconscious gesture of male

bonding a la russe, a moment of Russian behavioral authenticity—after

all, "real" American men do not kiss—or a planned effect. Kinskey is dead, so I cannot ask him to corroborate my

conjecture that it was the former, although very likely he would not have

remembered what had motivated him originally. My point in retelling this small

anecdote is to show the slippery relation between invented and authentic

Russianness, between simulacra and their originals, not only in the movies but

also in the émigré community. But as Beth Holmgren shows in her essay, Kinskey, like Misha Auer, would develop a Hollywood

identity as well, which contributed to his and Auer's long-lasting success in

the movies. Successful Russians ultimately had to transcend their Russian

roles.

Even though the Hollywood Russians may have

considered it their cultural mission to "accurately" reproduce the

Russian past and their ethnic identity on the screen, the bottom line reveals

that just about everything was for sale. This included not only objects with

the aura of authenticity but also their own shadows: aristocrats played

imposters; imposters—aristocrats; White Army officers—Bolsheviks, not just

Whites. The White officer and émigré poet Alexander Woloschin

played the young Stalin in Last Command. These facts, however, do not

negate either the community's or Hollywood's concern with the reproduction of

authenticity on the screen. Their motives were, of course, different.

Hollywood's concern with authentic representation, which the Russians typically

viewed as sham, was overtly "capitalist"; that is, promotional, and

typically simulated, in short—kitsch. The studios' motivation for creating the

aura of authenticity was that movie audiences preferred true stories to

fabricated ones, but "forged" provenances more than satisfied the

film-goers' scopic desire. For Russians, authenticity

was a matter of identity, even if it had been infiltrated by kitsch, their own

or the film industry's. Even when their notions of

authenticity were related to the émigré fantasy of return, new American forms

of social prestige—not to speak of economic necessity—began to inform their

self-identities. They would slowly abandon prerevolutionary rank and title and

what the community had claimed as authentically Russian. During the 1930s, even those émigrés most committed

"See Tsivian,

"Leonid Kinskey," 175-80.

210 Olga

Matich

to the White cause started unpacking their symbolic

suitcases, which they had kept ready for a speedy return to their homeland.

The consideration

of the fine line between simulacra and their originals (like the Holy Virgin

Cathedral) reveals the inextricability of the former from "authentic"

objects, exposing authenticity as a continuum just as dependent on economic and

aesthetic considerations as are simulacra. The relationship between the

sentimental kitsch deployed in Hollywood's "Russian genre" and its

nostalgic émigré variety reveals a similar continuum, despite the Russian

film-goers' rejection of the former as ignorant or willful misrepresentation of

their homeland and its cultural values.

WILEY

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood

The White Emigration Goes Hollywood

Author(s): Olga Matich

Source: The Russian Review, Apr., 2005, Vol. 64, No. 2 (Apr., 2005), pp. 187-210

Published by: Wiley on behalf of The Editors and

Board of Trustees of the Russian Review

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3664507

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on .TSTOR for this article:

https://www.

jstor.org/stable/3664507?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to .TSTOR

to access the linked references.

J'STOR is a

not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover,

use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We

use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate

new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR,

please contact support@jstor.org.

J'STOR is a

not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover,

use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We

use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate

new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR,

please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use

of the J'STOR archive indicates your acceptance of

the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms

|

|

Wiley is collaborating with J'STOR

to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Russian Review

|

|

JSTOR

|

|

![]() HOLLYWOOD RUSSIA

HOLLYWOOD RUSSIA